For decades, large mining corporations have used two loopholes in the Clean Water Act to dump massive amounts of toxic tailings and other waste into America's most pristine streams, lakes, and wetlands.

These are the waters from which we drink, in which our children swim, and which support our fish and wildlife such as grizzly bears in Bristol Bay, Alaska.

The hardrock mining industry is the single largest source of toxic waste and one of the most destructive industries in the country. Today's industrial-strength mining involves the blasting, excavating, and crushing of many thousands of acres of land and the use of huge quantities of toxic chemicals such as cyanide and sulfuric acid. The mines that produce our gold, silver, copper, and uranium are notorious for polluting adjacent streams, lakes, and groundwater with toxic by-products.

The Environmental Protection Agency estimates that 40 percent of the watersheds in the western United States are contaminated by pollution from hard rock mines.

Toxic spills and acid mine drainage kill fish and wildlife, poison community drinking water, and pose serious health risks. Adding insult to injury, the American public receives very little in exchange for the use and destruction of the public lands where many mines are located. Most mine developers are owned by foreign corporations and, unlike other extractive industries, the hardrock mining industry does not pay royalties for minerals taken from federal public lands. What's more, the public is generally on the hook for the clean-up of abandoned mines. It is estimated that there are a half million abandoned mines across the country and that taxpayers will have to pay $32 to $72 billion to clean up the sites.

There is not a single solution to the problems posed by hardrock mining, but one obvious step is to stop mines from dumping their toxic wastes in our lakes, rivers, and wetlands. Open pit mines create an enormous amount of waste. It has become a common industry practice over the last 30 years for mines to dam up the nearest river valley and treat wetlands and streams impounded by the dam as a toxic waste dump.

In theory, the Clean Water Act should halt this destructive practice. One of the primary goals of the act was to prevent the use of the nation's waters as disposal sites for industrial wastes. Unfortunately, there are two "loopholes" in the regulations implementing the Clean Water Act that have allowed mine developers to circumvent the purpose of this critical law.

Controversial projects such as the proposed Pebble mine in Alaska, Montanore mine in Montana, PolyMet mine in northern Minnesota, Mt. Emmons mine in Colorado, Haile mine in South Carolina, and numerous existing mines in the West and Appalachia are relying on these loopholes to cut costs and justify extensive environmental damage. While discharging wastes into wetlands, streams and lakes may be convenient for mining companies, it is not a necessary way of doing business.

Almost 30 years ago, the EPA found that mines could operate profitably without discharging their wastes into the nation's waters. The agency adopted a zero discharge standard for mines using cyanide and similar processes to extract metals such as gold and copper. That standard, if applied today, would prohibit open pit hard rock mines from "storing" their wastes in our waters.

U.S. Energy is proposing a large-scale molybdenum (a silvery white metal) mine in central Colorado on the flanks of the iconic Red Lady, otherwise known as Mt. Emmons. To be located just a few miles upstream from the ski town Crested Butte, it would transform a landscape renowned for its backcountry skiing, hiking, and fly fishing into a wasteland covering hundreds of acres, with land stripped to bedrock and strewn with toxic waste tailings ponds.

The Mt. Emmons mine would generate 6,000 tons of mined ore per day for 10.5 years, requiring extensive construction of tailings dump sites in the headwaters of Ohio and Carbon Creeks, a vast industrial complex of mills, slurry pipelines and roadways, and one or more tailings impoundments of 200 acres bounded by 200 feet tall dams.

This would have major impacts upon the local watershed, including:

U.S. Energy is already paying close to two million dollars a year to clean up toxic mining waste from the Keystone mine, a heavy metal mine at the same location as the proposed Mt. Emmons mine. The Keystone mine left a legacy of collapsed tailings dams and acid mine drainage, jeopardizing water quality in Coal Creek and threatening local drinking water supplies. Water flowing from the Keystone mine now requires costly and complex treatment before it can be discharged to Coal Creek.

With the same mining company operating a second mine in the same fragile watershed--but at a much greater scale—the impacts might not only affect the local environment and residents of Crested Butte; the area's network of pristine streams and wetlands could carry pollutants from the Mt. Emmons mine downstream to the town of Gunnison and eventually to Blue Mesa Reservoir, the largest body of water in Colorado.

As a nation, we decided that industries should not be able to profit from polluting the waters that sustain America's communities, fish, and wildlife. Help us close the two loopholes in the Clean Water Act that encourage irresponsible mining practices and irresponsible mines such as the Mt. Emmons mine in Colorado.

Read the Fact Sheet: Mt. Emmons Mine, Colorado (PDF)

Alaska’s Bristol Bay region, one of America’s most spectacular places and home to the world’s largest runs of sockeye salmon, is being targeted for large-scale mineral development. The Pebble gold and copper mine—planned for the headwaters of Bristol Bay’s best wild salmon rivers--would be the largest open pit mine in North America. It would scar this wilderness landscape forever and could destroy the salmon that make Bristol Bay unique.

The Pebble open pit gold and copper mine puts at risk the most spectacular and abundant ecosystem in North America. The region’s pure waters, healthy habitat, and breathtaking wilderness setting generate millions of dollars for the local economy by sustaining a thriving commercial fishery, attracting trophy salmon and trout anglers from all over the world, and supporting the centuries-old subsistence lifestyle of Alaska Natives.

Preliminary plans indicate that:

One of the most important components of a healthy, sustainable fishery is clean water. Sockeye, in particular, require not only pristine rivers and creeks to spawn, but also large, freshwater lake systems where they spend time as juveniles before heading to sea.

For thousands of years, Bristol Bay has been untouched by development, providing optimal conditions for returning salmon. Up to forty million sockeye salmon return to this watershed each year, contributing over $400 million per year to the Alaskan economy.

Toxic by-products are an inevitable result of open pit mines like the proposed Pebble Mine. This puts salmon at great risk, as they are highly sensitive to the slightest increases in certain metals like copper, interfering with their sense of smell, direction, and ability to evade predators.

Bristol Bay’s salmon are the foundation of a vibrant community of wildlife that includes bears, wolves, moose, caribou, and waterfowl.

Read the Fact Sheet: Pebble Mine, Alaska (PDF)

Additional Fact Sheet: Tribes and Hardrock Mining (PDF)

Take the Clean Earth Challenge and help make the planet a happier, healthier place.

Learn MoreA groundbreaking bipartisan bill aims to address the looming wildlife crisis before it's too late, while creating sorely needed jobs.

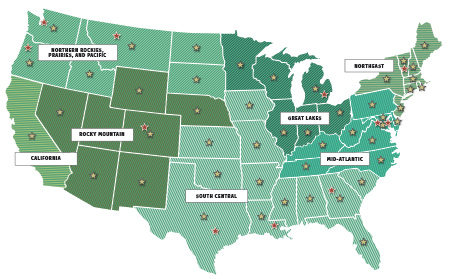

Read MoreMore than one-third of U.S. fish and wildlife species are at risk of extinction in the coming decades. We're on the ground in seven regions across the country, collaborating with 52 state and territory affiliates to reverse the crisis and ensure wildlife thrive.