The Farm Bill is one of the most important federal policies affecting conservation and wildlife habitat. It offers the single largest source of funding for conservation on private lands.

The Farm Bill is America’s largest investment in conservation on private and working lands and therefore the best opportunity for farmers and ranchers to better steward the resources that support our nation’s food supply, reverse natural habitat destruction, and improve resiliency. In 2021, Farm Bill-funded conservation programs touched over 45 million acres, an area larger than the entire state of Oklahoma.

Working with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, farmers, ranchers, foresters, and other private landowners can conserve, protect, and restore wildlife and pollinator habitat, sensitive grasslands and wetlands, adapt and mitigate the effects of climate change, improve soil health, increase the quality and quantity of water, and create more resilient communities.

It is critically important for the 2023 Farm Bill to build on past successes with robust conservation funding to address the increasing threats facing our ecosystems, wildlife, and people. Read about the National Wildlife Federation’s 2023 Farm Bill priorities here.

What is the Farm Bill?

The federal Farm Bill has existed in different forms since the age of the Dust Bowl and comes up for reauthorization approximately every five years. The latest Farm Bill passed by Congress was The Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 (the 2018 Farm Bill), which funds USDA programs through 2023. Read more about the National Wildlife Federation’s analysis of the 2018 Farm Bill and our press statement on its passing.

Farm Bill Conservation Programs

Several different Farm Bill conservation programs have helped improve wildlife habitat in the U.S. Learn about the unique functions of each program below:

The Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) pays farmers annual rental payments under 10-15 year contracts, to take marginal, environmentally sensitive land out of rowcrop agriculture and plant it with conservation cover. The program also pays up to half the cost of establishing conservation practices that address soil erosion, water quality, wetland and forest enhancement, and wildlife management. Examples of these practices include establishing vegetative cover or trees on erodible cropland, planting native grasses, thinning or conducting controlled burning of pine forests, and placing filter strips along stream banks to stem polluted runoff and provide habitat for wildlife.

The Agricultural Conservation Easement Program (ACEP) was created by the Agricultural Act of 2014. It combines the former Wetland Reserve Program (WRP) , the Grassland Reserve Program (GRP), and the Farm and Ranch Lands Protection Program (FRPP) in to two tracks: a wetland easements component and an agricultural land easements component. Through ACEP, eligible conservation partners including non-governmental organizations, private landowners, Tribes, land trusts, and others can leverage federal funding to preserve wetland and agricultural lands in long term easements.

The Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) rewards agricultural producers for environmentally-friendly measures they are willing to undertake on the lands that they keep in production. CSP offers payments to producers who maintain a high level of conservation on their land, and who agree to adopt higher levels of stewardship. Eligible lands include cropland, pastureland, rangeland and non-industrial forestland.

Similar to CSP, the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) provides technical and financial assistance to farmers and ranchers to implement conservation practices on their lands. Practices are based on a set of national priorities that are adapted to each state. These priorities include: reduction of point- and non-point source pollution to watersheds and groundwater; water conservation; reduction of soil erosion; and promotion of wildlife habitat for at-risk-species. The Wildlife Habitat Incentive Program (WHIP) was combined with EQIP in the 2014 Farm Bill. WHIP was a voluntary program that pays up to 75 percent of the cost to private landowners of enhancing wildlife habitat on their land. As of 2018, a minimum of 10 percent of EQIP funding goes to wildlife practices.

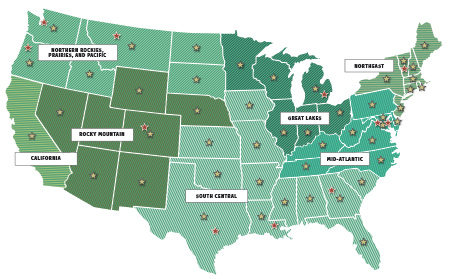

The Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP), created in the 2014 Farm Bill, establishes a way for conservation partners, USDA, and state agencies to jointly provide landowners with conservation assistance by designing and installing practices on working lands. RCPP is partially funded through CSP, EQIP, and ACEP to leverage private funding. The program has been hampered by overly burdensome administrative requirements but holds great promise for scaling conservation in a cost-effective manner.

How Farm Bill Conservation Programs Benefit Soil, Water, Wildlife, and Climate

Many conservation programs established through the federal Farm Bill offer solutions to farmers through technical advice, cost sharing, and land payments to reduce the environmental impacts of agriculture. These programs help prevent complete degradation of numerous ecosystems, wildlife habitats, and watersheds. Farm Bill conservation programs offer some of the most cost-effective solutions available to producers and private landowners, while providing vital environmental protection and employment opportunities in rural America.

For example, through the CRP, farmers and landowners practicing erosion and nutrient loss prevention from farmlands receive payments when they take their land out of production and plant perennial grasses. Permanent land cover of perennial grasses is beneficial because it prevents the use of chemicals—reducing agricultural emissions and nutrient runoff—increases carbon sequestration, and the grasses compete better against weeds and insects.

For example, through the CRP, farmers and landowners practicing erosion and nutrient loss prevention from farmlands receive payments when they take their land out of production and plant perennial grasses. Permanent land cover of perennial grasses is beneficial because it prevents the use of chemicals—reducing agricultural emissions and nutrient runoff—increases carbon sequestration, and the grasses compete better against weeds and insects.

CRP also benefits wildlife by incentivizing farmers to provide vital cover within agricultural working lands that support numerous species, such as grassland birds or waterfowl. When CRP fields are near wetlands, the potential to increase duck production is greater. Species such as mallards, gadwalls, and northern pintails can benefit from CRP cover immensely.

Other programs, such as CSP, pay farmers already implementing conservation practices and provides an incentive to implement further conservation practices for the duration of a contract. Additionally, EQIP provides cost-share and technical assistance to farmers to help them implement numerous practices that improve waterways, reduce nutrient runoff, capture methane emissions, and it provides funds for implementing cover crops or transitioning to organic production.

Though just a few benefits of Farm Bill conservation programs are described, there are many opportunities for farmers and landowners to help improve soil, water, wildlife, climate, and local communities.

Farm Bill Success: Greater Sage-Grouse

As of 2022, EQIP partnered with 2500 ranchers to help restore 9 million acres of sagebrush habitat through the Sage Grouse Initiative across 11 states.

As of 2022, EQIP partnered with 2500 ranchers to help restore 9 million acres of sagebrush habitat through the Sage Grouse Initiative across 11 states.

The signature greater sage-grouse roams around the sagebrush steppe of Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, Nevada, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington. Thanks to Farm Bill conservation programs such as EQIP, encroaching threats (i.e. conifers, high-risk fences) to the greater sage-grouse are removed and new grazing systems that increase nesting cover—like the rest-rotation systems—are installed.

Wetland Conservation in the Farm Bill

The Importance of Swampbuster

As Congress drafts a new Farm Bill, it’s important to reflect on the significance of wetlands and understand how proposals to modify Swampbuster rules may impact wetland resources and the many benefits they provide.

Conservation Funding

The Farm Bill authorizes spending for many different programs, including conservation, nutrition, energy, and crop insurance. Although it makes up a much smaller portion of the bill, the conservation title provides the largest source of funding for conservation on private lands.

Farm Bill conservation programs provide technical and financial assistance to enable farmers, ranchers, and foresters to adopt practices that build soil health, improve water quality and quantity, sequester carbon, and enhance and protect habitat for wildlife. However, due to high demand, these programs are often oversubscribed, with many more applicants than funding available. There is a need for increased support for conservation programs to ensure producers have the resources they need to adopt conservation practices on their lands.

The Inflation Reduction Act provided a historic investment of $20 billion for climate-smart agriculture and conservation programs. The 2023 Farm Bill should protect and build on this historic investment. Read more about the Inflation Reduction Act and what it means for agriculture conservation.

The National Wildlife Federation works to ensure that there is adequate funding for programs to help farmers install and maintain conservation practices on their land, as well as land set aside for conservation and wildlife uses. There are two major processes that affect how much funding Farm Bill programs receive: authorization and appropriations. Authorization, through mandatory and discretionary funding, and appropriations are the two important steps in the process of funding Farm Bill programs. The National Wildlife Federation works to support robust funding for conservation programs in both steps of the process.

Approximately every five years, the House and Senate Agriculture Committees write a Farm Bill that sets initial funding levels and authorization of Farm Bill programs. The appropriations process, on the other hand, is an annual process governed by the House and Senate Appropriations Committee. Funding for Farm Bill programs in the appropriations process is often significantly reduced during annual appropriations.

For some Farm Bill programs, Congress used the traditional method of funding—authorizing a maximum amount for each year that must then be appropriated annually. This is often referred to as "discretionary funding."

For most of the major USDA conservation programs, the Farm Bill provides "mandatory" funding for each year. Mandatory funding does not rely on annual Congressional appropriations bills; however, it is subject being reduced during the appropriations process. These cuts are known as "Changes in Mandatory Program Spending," or CHIMPS.

Mandatory funding provides a road map for conservation programs for the life of each Farm Bill. In some cases, the program size is determined by acres, rather than dollars. For example, the Conservation Reserve Program whose allocated acres have fluctuated widely since the program was created in 1985. For other programs, the Farm Bill provides a set level of mandatory funding each year, such as various working lands programs (EQIP, CSP, RCPP).

Even though most conservation programs have "mandatory" funding, Congress can still reduce the amount of funding authorized in the Farm Bill by limiting the funds, or capping the acres that can be enrolled through the annual budget or appropriations bills. Such Changes in Mandatory Program Spending, or CHIMPS, have been responsible for the increasing cuts to conservation programs in recent years.

Farm Bill conservation programs are highly popular with farmers and beneficial to taxpayers. The National Wildlife Federation is working to ensure that conservation does not continue to be limited due to lack of funding.

For example, through the CRP, farmers and landowners practicing erosion and nutrient loss prevention from farmlands receive payments when they take their land out of production and plant perennial grasses. Permanent land cover of perennial grasses is beneficial because it prevents the use of chemicals—reducing agricultural emissions and nutrient runoff—increases carbon sequestration, and the grasses compete better against weeds and insects.

For example, through the CRP, farmers and landowners practicing erosion and nutrient loss prevention from farmlands receive payments when they take their land out of production and plant perennial grasses. Permanent land cover of perennial grasses is beneficial because it prevents the use of chemicals—reducing agricultural emissions and nutrient runoff—increases carbon sequestration, and the grasses compete better against weeds and insects. As of 2022, EQIP partnered with 2500 ranchers to help restore 9 million acres of sagebrush habitat through the Sage Grouse Initiative across 11 states.

As of 2022, EQIP partnered with 2500 ranchers to help restore 9 million acres of sagebrush habitat through the Sage Grouse Initiative across 11 states.